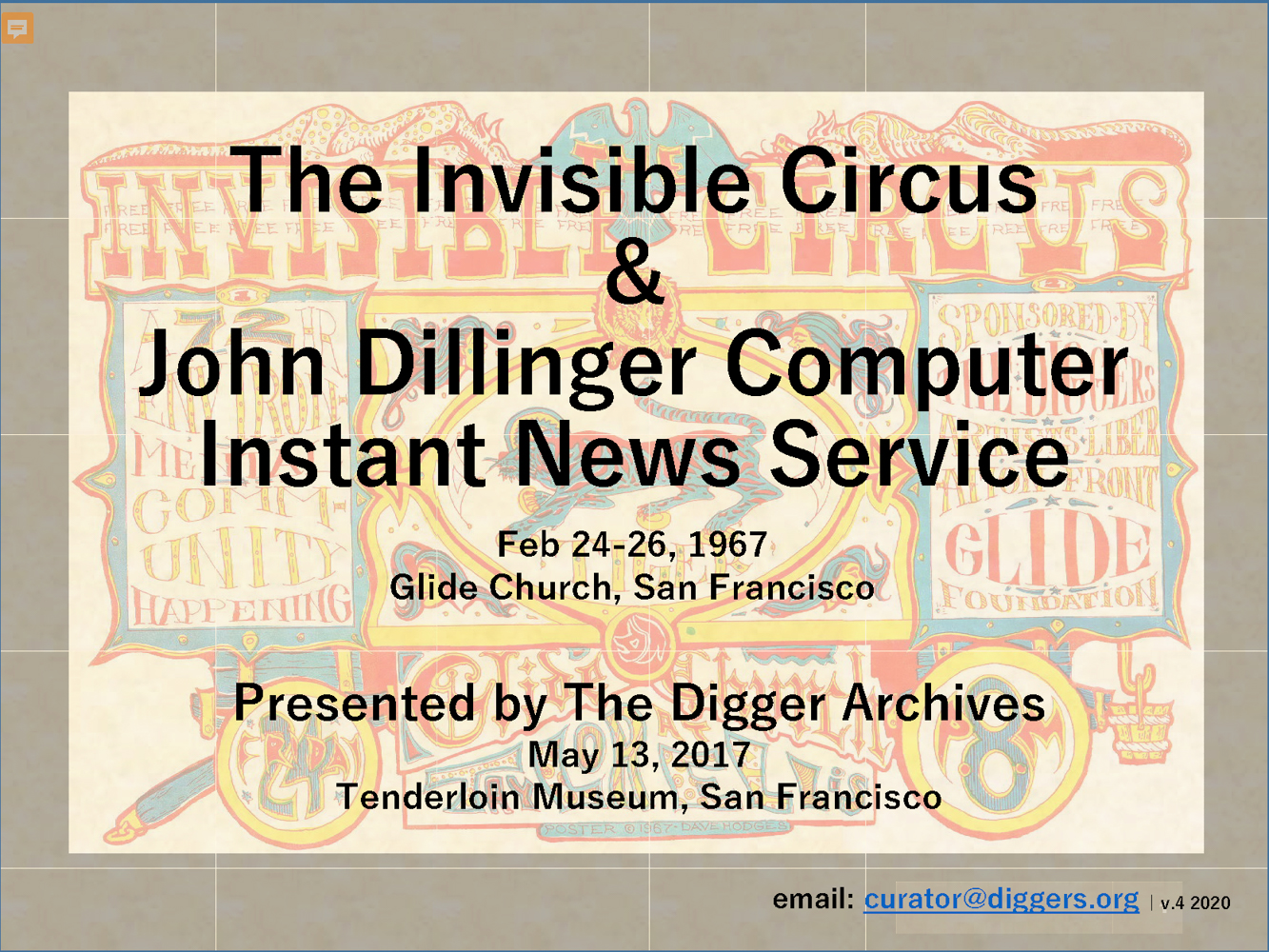

Recently, I was able to digitize the interviews that Alice Gaillard and Céline Deransart conducted in 1998 in the making of the documentary Les Diggers de San Francisco. Among the dozens of people Alice and Céline interviewed was Arthur Lisch, one of the early San Francisco Diggers who played an important role, especially in his contacts with the liberal religious community in San Francisco. Arthur can be seen in several of William Gedney‘s photos from the first weeks of the Digger Feeds and the Digger Free Frame of Reference free stores. The interview of Arthur did not make it into the final cut of Alice’s and Celine’s film, so its recent discovery is all that more valuable and remarkable.

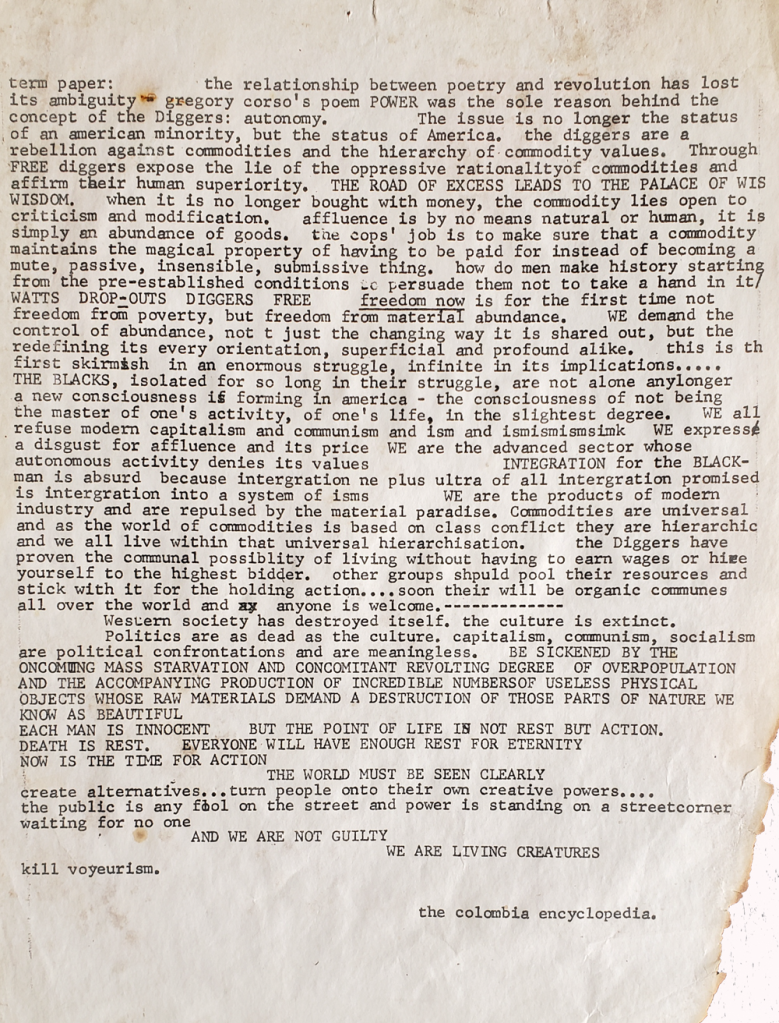

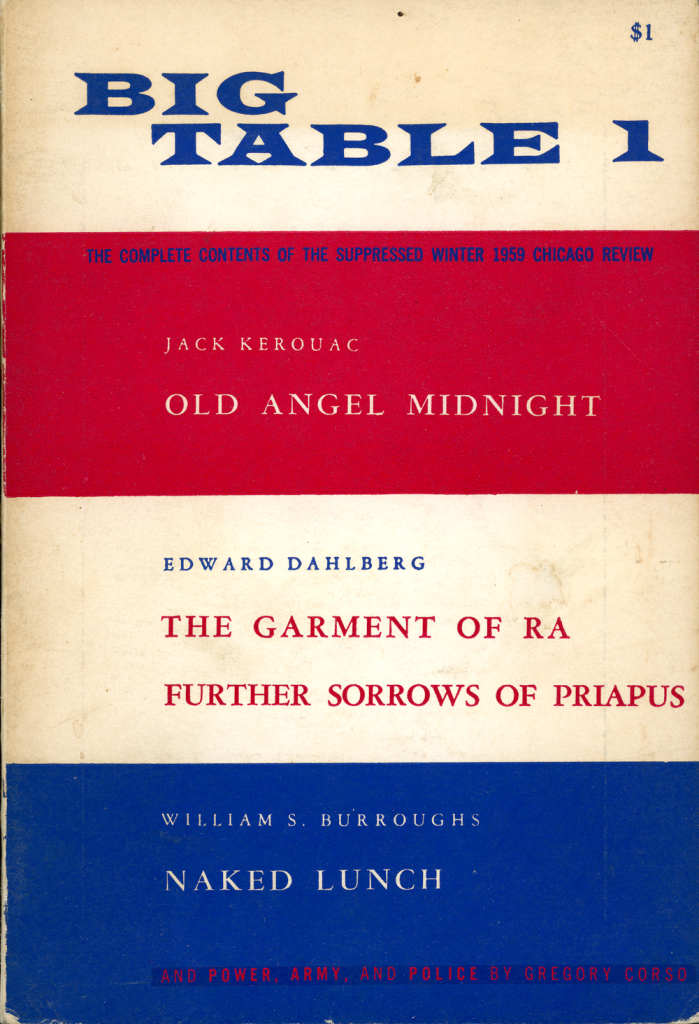

I say remarkable because there are things in the interview which have shined light on aspects of Digger history that have remained murky until now. Above all, Arthur demonstrates the influence of the original Diggers of 1649 in Surrey, England. Over the years, I’ve heard people say that the English Diggers played a minor influence on their latter-day namesakes. Reading Arthur’s interview will prove that suggestion false. Gerrard Winstanley’s True Leveller (Digger) writings from 1649+ obviously had an immense effect. Up until now, it has only been Emmett Grogan’s account in Ringolevio, along with several of the ephemeral statements in Communication Company street sheets, that testified to this influence. Now, we can see in Arthur’s words, how completely the English Digger ideas were understood and transplanted into the 1960s counterculture. Here is an excerpt from Arthur’s interview, describing the living circle he had inscribed on the earth in the midst of a public park thirty years after the Summer of Love:

“The circle is a latter day initiative that has to do with the Digger philosophy — not just the Digger philosophy, but the original ‘True Leveller’ philosophy. The True Leveller philosophy was even further called the Christ Levellers. And the idea of the True Levellers was that the common land belongs to the common people who choose to come on that land, care for the land, love the land, work the land. So in the sense that the initiative was taken by me 10 years ago, to establish this circle, this is, 30 years later, a Digger initiative — this is a True Leveller initiative. It is, because I say it is [chuckles], and because that’s my intention. It’s a spiritual scientific experiment: to see if a circle is drawn on the earth, if people will come, and if they will fill that circle with care, concern, love, work — activity.”

We can see from this activity that Arthur was creating a vision of the original English Digger notion of the Earth as a Common Treasury for all. Arthur had read and understood Gerrard Winstanley’s writings so completely that he was on a lifelong mission to encapsulate those ideas. He also had obviously read about that period of English history known as the English Civil War because, later in the interview, he talks about the common origins of the Quakers and the Diggers at that time. I think this interview is strong evidence that the influence of the English Diggers on their twentieth-century namesakes was profound. Up until now, Emmett Grogan had been the prime example. Now we can see that Arthur Lisch is another. (Still another example is that of Irving Rosenthal, founder of the Sutter Street (Kaliflower) Commune, but his ‘conversion‘ to Digger philosophy happened two years later.)

Arthur relates his work on the Earth Circle to the poster that the Diggers produced in the Winter of 1968 with the image of two Tong warriors standing on a street corner and the only text on the poster being the I Ching character for the hexagram “Revolution” and the words 1% Free. Ever since this poster appeared mysteriously overnight on walls and surfaces scattered around San Francisco, people were left scratching their heads wondering at its meaning. Peter Berg described the effect of this, what some considered menacing, image. In one of his interviews, Berg said, “The … merchants thought it was a profiteering scheme. They thought 1% Free meant we were the mafia. We’d beat them up if they didn’t give it to us [laughter].” Arthur Lisch describes his own take on 1% Free:

“[T]he initial beginning [of the Earth Circle] goes back to that poster that was made that said ‘1% Free’ … [T]he idea of being “1% free” means that, to me, we can take that initiative, we can take that step, and then things will fall into place around it. This was initially 1% free. It’s not 100% free now, but so many people have come here, worked here, care for the place, they’ve claimed this circle of land in the name of community and the name of the sacred in life, in the name of a higher way of being. … In other words, to see the higher in each other, for each of us to see what is better, what is hopeful, what is possible in each other. And this small circle is dedicated to that.”

Another important piece of the interview of Arthur is something he mentions in relation to Emmett Grogan. “I remember Emmett Grogan writing ‘The Ideology of Failure.’ I think he mentioned me in a little essay about going out to Hunter’s Point in San Francisco, with a sculpture that was installed there where a 14-year-old was shot running across the field by the police. And I went out there every day for a number of months to vigil and to meet with people and to try to make a park, back in 1967. And Emmett mentioned that, and the idea that you need to be anonymous, you need to be not prideful about your work, you just need to offer your work and your activity.”

“The Ideology of Failure” appeared in the Berkeley Barb in November, 1966, a month after Emmett and Billy Murcott began bringing hot stew to the Panhandle for daily free feeds. The article was signed “George Metesky” and it was the second article about the Diggers that was signed thus. George Metesky, of course, was a pseudonym (the real George Metesky was serving a sentence for the bombings he had carried out over a sixteen-year span in New York where he had been dubbed the “Mad Bomber” by local newspapers).

Over the years, I have tried to determine who wrote the early Digger articles that were signed pseudonymously, specifically “The Ideology of Failure” which is a crucial and foundational text for understanding the Diggers. There has never been a clear-cut answer until now. Emmett Grogan was the natural and logical choice (many clues in Ringolevio, not just to his fascination with the Mad Bomber, but key words and phrases he used). But others were proposed as the author — Peter Berg, Peter Coyote, a collaboration between Emmett and Billy, even one very serious suggestion that it was Abbie Hoffman. With this interview of Arthur, the balance has tipped. Emmett Grogan was the author of this piece and most likely of all the Digger “George Metesky” articles.

This whole line of speculation brings up a topic that is close to my heart. Anonymity. The Diggers maintained (at least at the outset) a cloak of anonymity and protecting that veil was one of the games they played with their audience. The famous story of the two reporters attempting to interview the “manager” of the Trip Without A Ticket is an example. Both reporters arrived independently at the free store. The Diggers took each reporter aside and swore each to discretion if they wanted to interview the manager who did not want to acknowledge himself as such. Then the Diggers introduced the two reporters who interviewed each other for some minutes before realizing the caper.

For historians, the question is to what extent we should honor the veil of anonymity or pierce it. Half a century after the events in question, I think there are valid historical reasons to pierce the veil.