The past several days have brought snow accumulations to the San Francisco Bay Area rarely if ever seen — Mt. Tamalpais, Mount Hamilton, Mount Diablo ring the Bay like crystal jewelry suspended in memory. A friend forwarded an article about Gary Snyder which was a joy to read (“Man. Verses. Nature” by Hillary Louise Johnson, Sactown Magazine, Sept-Oct 2022, https://www.sactownmag.com/man-verses-nature-gary-snyder/). Though the writer mentioned several of Snyder’s best known works, there was one that was notable for its absence. This was a broadside published in 1975 which is a paean to that neighborhood in San Francisco with some of the best weather on the planet. “North Beach” resonates with places of the mind, places where synergy combines to further human consciousness of the natural world.

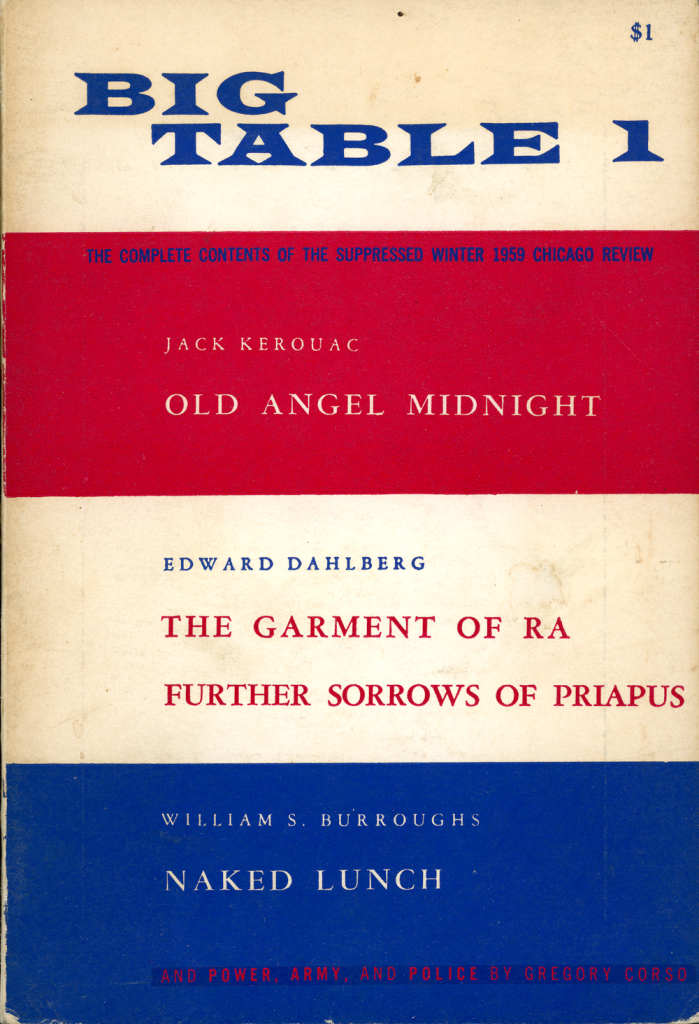

In thinking about the history of the Sixties, North Beach takes on a significance similar to the outcroppings of limestone that dot the surface of that neighborhood. The truths that the Beat poets uncovered in the 1950s became the ground on which the 60s radicals continued the social assault.

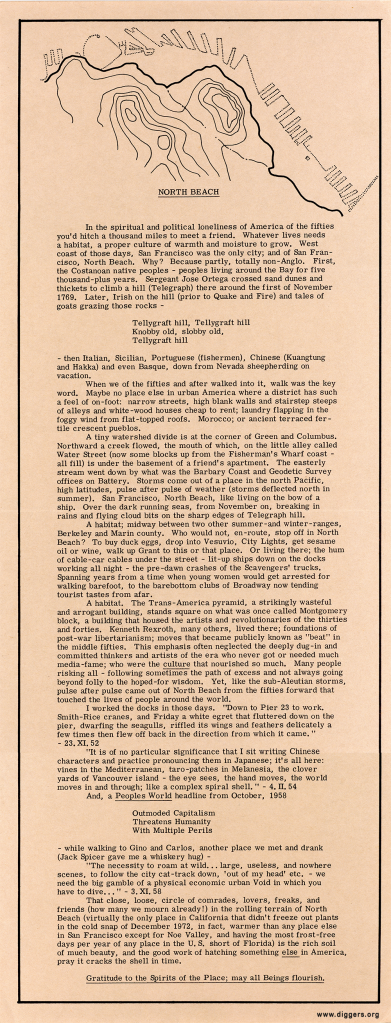

Here then is the (semi-anonymous) manifesto/ode/paean to “North Beach” (published by Canessa Gallery, 1975).

[transcription:]

North Beach

In the spiritual and political loneliness of America of the fifties you’d hitch a thousand miles to meet a friend. Whatever lives needs a habitat, a proper culture of warmth and moisture to grow. West coast of those days, San Francisco was the only city; and of San Francisco, North Beach. Why? Because partly, totally non-Anglo. First, the Costanoan native peoples — peoples living around the Bay for five thousand-plus years. Sergeant Jose Ortega crossed sand dunes and thickets to climb a hill (Telegraph) there around the first of November 1769. Later, Irish on the hill (prior to Quake and Fire) and tales of goats grazing those rocks —

Tellygraft hill, Tellygraft hill

Knobby old, slobby old,

Tellygraft hill

— then Italian, Sicilian, Portuguese (fishermen), Chinese (Kuangtung and Hakka) and even Basque, down from Nevada sheepherding on vacation.

When we of the fifties and after walked into it, walk was the key word. Maybe no place else in urban America where a district has such a feel of on-foot: narrow streets, high blank walls and stairstep steeps of alleys and white-wood houses cheap to rent; laundry flapping in the foggy wind from flat-topped roofs. Morocco; or ancient terraced fertile crescent pueblos.

A tiny watershed divide is at the corner of Green and Columbus. Northward a creek flowed, the mouth of which, on the little alley called Water Street (now some blocks up from the Fisherman’s Wharf coast — all fill) is under the basement of a friend’s apartment. The easterly stream went down by what was the Barbary Coast and Geodetic Survey offices on Battery. Storms come out of a place in the north Pacific, high latitudes, pulse after pulse of weather (storms deflected north in summer). San Francisco, North Beach, like living on the bow of a ship. Over the dark running seas, from November on, breaking in rains and flying cloud bits on the sharp edges of Telegraph hill.

A habitat; midway between two other summer-and winter-ranges, Berkeley and Marin county . Who would not, en-route, stop off in North Beach? To buy duck eggs, drop into Vesuvio, City Lights, get sesame oil or wine, walk up Grant to this or that place. Or living there; the hum of cable-car cables under the street — lit-up ships down on the docks working all night — the pre-dawn crashes of the Scavengers’ trucks. Spanning years from a time when young women would get arrested for walking barefoot, to the barebottom clubs of Broadway now tending tourist tastes from afar.

A habitat. The Trans-America pyramid, a strikingly wasteful and arrogant building, stands square on what was once called Montgomery block, a building that housed the artists and revolutionaries of the thirties and forties. Kenneth Rexroth, many others, lived there; foundations of post-war libertarianism; moves that became publicly known as “beat” in the middle fifties. This emphasis often neglected the deeply dug-in and committed thinkers and artists of the era who never got or needed much media-fame; who were the culture that nourished so much. Many people risking all — following sometimes the path of excess and not always going beyond folly to the hoped-for wisdom. Yet, like the sub-Aleutian storms, pulse after pulse came out of North Beach from the fifties forward that touched the lives of people around the world.

I worked the docks in those days. “Down to Pier 23 to work, Smith-Rice cranes, and Friday a white egret that fluttered down on the pier, dwarfing the seagulls, riffled its wings and feathers delicately a few times then flew off back in the direction from which it came.” 23.Xl. 52

“It is of no particular significance that I sit writing Chinese characters and practice pronouncing them in Japanese; it’s all here: vines in the Mediterranean, taro-patches in Melanesia, the clover yards or Vancouver island – the eye sees, the hand moves, the world moves in and through; like a complex spiral shell. ” — 4. II . 54

And, a Peoples World headline from October, 1958

Outmoded Capitalism

Threatens Humanity

With Multiple Perils

— while walking to Gino and Carlos, another place we met and drank (Jack Spicer gave me a whiskery hug) —

“The necessity to roam at wild . . . large, useless, and nowhere scenes, to follow the city cat-track down, ‘out of my head’ etc. — we need the big gamble of a physical economic urban Void in which you have to dive … ” — 3, XI. 58

That close, loose, circle of comrades, lovers, freaks, and friends (how many we mourn already!) in the rolling terrain of North Beach (virtually the only place in California that didn’t freeze out plants in the cold snap of December 1972, in fact, warmer than any place else in San Francisco except for Noe Valley, and having the most frost-free days per year of any place in the U. S. short of Florida) is the rich soil of much beauty, and the good work of hatching something else in America, pray it cracks the shell in time.

Gratitude to the Spirits of the Place; may all Beings flourish.